Welcome to Mauritania!

Mauritania is a transit route, a crossroads of cultures, an amazing meeting of the Maghreb and Black Africa, a space of intermingling of peoples and civilizations. Its population, of Muslim religion in its totality, is composed of communities of both Arab-Berber and Negro-African origins, whose history has closely entangled their destinies.

The “socio-ethnic” groups (Moors, Soninkés, Haalpulaar’en and Wolofs) which compose the country remain deeply entrenched to their traditional lifestyles while sharing similar or even identical social systems and cultural and moral values and also having cultivated socio-cultural specificities that give to the cultural diversity of the country a particular charm.

This unity / diversity of cultures blends in a variety of natural environments. Mauritania is subdivided into four major ecological zones: the Saharan zone; the Sahelian zone; the river valley; and the coastline.

Each of these zones is rich of its own diversity: the large dunes of the desert and the embedded rocky heights of the Adrar and the Tagant dressed with greeneries springing from rocks; the spotless beaches of the coastline extending to infinity, and the paradise of the birds of the Banc d’Arguin; the lazy course of the river with its curve runs and banks hosting vibrant and colorful life.

Even though, we are only a few hours flight from Europe, we feel like we are at the end of the world when we are in many places of Mauritania. Mauritania is one of those countries in which we can still enjoy the infinite spaces, the feeling of a freedom without any restrictions or limits.

Come to discover this magnificent country, go to meet the nomadic populations, share with them very emotional moments around the ceremonial of the tea. Go to assault dunes on foot, on camel back or onboard all-terrain vehicle, Laze on its sandy beaches, behold the thrilling spectacle of thousands of birds of a thousand different species of the Banc d’Arguin. Walk the country up and down, and if fortune is on your side, you may encounter one of the last caravans that came from a distant past and who continue to unroll the ancient timeline that has forged the close links between the Sub-Saharan Africa and the Maghreb.

History of Mauritania

Early history

Mauritania’s contributions to the prehistory of western Africa are still being researched, but the discovery of numerous Lower Paleolithic (Acheulean) and Neolithic remains in the north points to a rich potential for archaeological discoveries.

In historical times Mauritania was settled by sub-Saharan peoples and by the Ṣanhājah Imazighen (Berbers). The region was the cradle of the Amazigh (singular of Imazighen) Almoravids, a puritanical 11th-century Islamic reform movement that spread an austere form of Islam from the Sahara through to North Africa. The main commercial routes that connected subsequent empires in Morocco with the south passed through Mauritania, carrying Saharan salt and Mediterranean luxury products such as fine cloth, brocades, and paper in exchange for gold. In the central desert, Chingueṭṭi, the fabled seventh great city of Islam, was one of the major caravansaries along these routes; another was Oualâta, situated to the south and east of Chingueṭṭi and renowned for the elaborately painted walls of the homes there.

It was along these routes that the Ḥassānī Arab tribes entered the western Sahara, and gradually an amalgamation of Arab-Amazigh, or Moorish, culture emerged. The Ḥassānī and Arabized Amazigh nomadic tribes formed several powerful regional confederations that claimed their origin in Amazigh or Arab ancestry and characterized themselves as pacific, religiously minded zawāyā (such as the Idaw ʿAish, said to be the original descendants of the Lamtunah tribe, and the Reguibat, who claim descent from the Prophet Muhammad) or the raiding, warrior Ḥassānī tribes (such as the Trarza and Brakna), respectively. The outcome of a famous conflict (or possibly a series of conflicts) between them in the mid-17th century, known today as Shurr Bubba (“the War of Bubba”), became a reference point for deciding political and social status in the southern Sahara.

European intervention

In 1442 Portuguese mariners rounded Cape Blanco (Cape Nouâdhibou) and six years later founded the fort of Arguin, whence they derived gold, gum arabic, and slaves. These same commodities later drew Spanish, then Dutch trade to the coast in the 17th century when gum arabic was found to be useful in textile manufacture. The French competed for access to this trade, first with the Dutch and, in the 18th century, with the English, and it was to the French that much of the Saharan coast was ceded in European treaties early in the 19th century. French claims to sovereignty over the hinterland were regularly disputed by the leaders (referred to as “amirs” or “commanders” by the French) of the regions of Trarza and, to the east, Brakna—named for the two Ḥassānī lineages that dominated the Sénégal River valley—who claimed territory on both sides of the Sénégal River. The French governor of the region, Col.

Louis Faidherbe, entered into treaty relations with the amirs in 1858, but France made little effort to exert control over southern Mauritania until the opening years of the 20th century. The “pacification” of Mauritania, as it was styled by the French military, continued until 1912, and the final battle to subdue a Reguibat band took place in 1934. The French nickname for the colony was “Le Grand Vide” (“the great void”); so long as the population was quiet, there was little evidence of a French presence. Moorish lineages were engaged on both sides of the colonial occupation, some assisting the French and others opposing their presence. Some who benefited from the French presence were well positioned to take on prominent political roles in 1958 when the first elected government under Moktar Ould Daddah negotiated membership in the French Community. The Islamic Republic of Mauritania was declared an independent state on November 28, 1960; it became a member of the United Nations in October 1961.

Struggle for post-independence stability

The small political elite that guided the independence movement was divided over whether the country should be oriented toward Senegal and Black, French-speaking Africa or toward nearby Arab Morocco and the rest of the Arab world. This was complicated by the fact that Morocco, under King Hassan II, waged an irredentist campaign—including temporary occupation of parts of the Mauritania—during the 1960s. The political direction under Ould Daddah was one of cautious balance between the country’s African and Arab roots; independence came with close ties to France and full participation in the Organization of African Unity (later the African Union [AU]) but also with membership in the Arab League in 1973. The political conflict of those early years continued to manifest itself decades later.

As Mauritania’s first postindependence president, Ould Daddah appeared securely established in spite of occasional strikes by miners and demonstrations by students, because his policies seemed attuned to a population that was largely tribal and engaged in agriculture or pastoralism. In 1969 Morocco’s King Hassan II had reversed his policy and recognized Mauritanian independence as part of his plan to gain control of what was then Spanish Sahara (now Western Sahara), and Morocco and Mauritania divided that country in 1976. The difficulties of suppressing the Saharawi independence movement led by the Polisario Front guerrillas in Mauritania’s portion of Western Sahara contributed to Ould Daddah’s downfall. In July 1978 he was deposed and exiled in a military coup led by the chief of staff, Col. Mustapha Ould Salek.

Ould Salek resigned his position in June 1979, and under his successor, Lieut. Col. Mohamed Mahmoud Ould Louly, Mauritania signed a treaty with the Polisario Front in August in an effort to disentangle itself from Western Sahara. This worsened relations with Morocco. Ould Louly was in turn replaced in January 1980 by the prime minister, Lieut. Col. Mohamed Khouna Ould Haidalla.

Presidency of Maaouya Ould Sidi Ahmed Taya (1984–2005)

In December 1984 Col. Maaouya Ould Sidi Ahmed Taya took over the presidency and the office of prime minister from Ould Haidalla in a bloodless coup, and Mauritania renewed diplomatic ties with Morocco in 1985, seeking again to resolve the dispute in Western Sahara.

Conflict with Senegal was another concern. Sparked by ethnic tension, economic competition, the struggle for herding rights along the Sénégal River, and long-smouldering resentment on both sides at the roles played by one another’s citizens in local economies, in 1989 Mauritania and Senegal both expelled tens of thousands of each other’s citizens, cancelled diplomatic relations, and teetered on the brink of war. Diplomatic ties were not reestablished until April 1992, and although efforts to repatriate the large refugee populations that had fled to their respective home countries were undertaken, by the early 2000s not all had yet returned.

Domestically, Ould Taya pursued an aggressive Arabization policy within the government as well as the educational system considered by many Black Mauritanians as prejudicial. Some of the president’s other initiatives were more widely accepted: he presided over a return to civilian government and the development of a multiparty system, opened the country to a relatively free press, and inaugurated a new constitution (1991) while cooperating closely with the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund in making structural adjustments and privatizing the economy. Ould Taya was subsequently victorious in the country’s first multiparty presidential election in 1992 and was reelected in 1997 and 2003. The election, however, drew allegations of fraud.

Coups of 2005 and 2008 and the return to stability

In August 2005, while Ould Taya was out of the country, army officers staged a successful coup. Col. Ely Ould Mohamed Vall, a former close ally of Ould Taya, emerged as the leader of the ruling Military Council for Justice and Democracy. He pledged that democracy would be restored, and in 2006 he presented a referendum on constitutional reforms. Voters overwhelmingly approved the changes, which included limiting presidents to two consecutive terms of five rather than six years. In the March 2007 presidential election, Sidi Ould Cheikh Abdallahi became Mauritania’s first democratically elected president.

Criticism against President Ould Abdallahi simmered in the months following his election, and tensions escalated in May 2008 when Ould Abdallahi appointed a number of ministers who had held important posts in Ould Taya’s government, some of whom had been accused of corruption. In July the parliament passed a vote of no confidence, which was followed by the departure of almost 50 ruling-party members of parliament in early August. On August 6, 2008, Ould Abdallahi dismissed a number of high-ranking army officials rumoured to have been involved in the parliamentary crisis, including Gen. Mohamed Ould Abdel Aziz, Commander of the Presidential Guard, and Gen. Mohamed Ould Chiekh Ghazouani, Chief of Staff of the National Army. In response the military promptly staged a coup and removed him from power. In December 2008 Ould Abdallahi was released after several months’ house arrest. With the continued failure of the military government to reinstate civilian rule, early the following year the AU imposed sanctions on Mauritania that included financial measures and a ban on travel. External pressures mounted on the military regime and led to a new round of elections in July 2009, when the coup leader, Ould Abdel Aziz, now a populist advocate for the poor, was affirmed in office, with Ould Ghazouani remaining as his chief of staff and right-hand confidant.

Ould Abdel Aziz’s presidency was marked by increased stability, security, and strong economic growth. His initiatives, moreover, brought improvement in living standards among the poor. But his policies were repressive, and opposition, expressed especially in the form of anti-slavery activism, was suppressed. In October 2012 he was shot, reportedly by accident; Ould Ghazouani acted as head of state while Ould Abdel Aziz underwent treatment in France. Despite rumours of his incapacitation, he returned to Mauritania six weeks later and resumed his presidency. He was elected to a second five-year term as president, with over 80 percent of the vote, in June 2014. The opposition boycotted the election, saying that the electoral process had been engineered to guarantee Ould Abdel Aziz an easy victory.

In 2017 a referendum suggested by Ould Abdel Aziz passed, abolishing the Senate and making changes to the Mauritanian flag. In his comments in support of the referendum, Ould Abdel Aziz characterized the Senate as redundant and expensive to maintain, but his opponents accused him of seeking to eliminate the Senate in order to ease the amendment of the constitution in his favour. Despite concerns that he would abrogate constitutional term limits, he did not seek a third term and instead endorsed a run by Ould Ghazouani in the 2019 election.

Ould Ghazouani won the election with just over half the vote, avoiding a runoff against one of several opposition candidates. His inauguration in August 2019 marked Mauritania’s first democratic transfer of power, notwithstanding his very close relationship with the outgoing president. Observers expected his presidency to mark a continuation of Ould Abdel Aziz’s policies.

People of Mauritania

Ethnic groups

The Moors constitute more than two-thirds of the population. About three-fifths of the Moorish population has Sudanic African origins and is collectively known as Ḥarāṭīn (singular Ḥarṭānī; sometimes referred to by the outside world as “Black Moors”). About two-fifths of the Moorish population self-identifies as Bīḍān (singular Bīḍānī, translated literally as “white”; “White Moors”), which indicates individuals of Arab and Amazigh (Berber) descent. The Ḥarāṭīn speak the same language as the Bīḍān and, in the past, were part of the nomadic economy. They served as domestic help and labourers for the nomadic camps, and, although some remain, they were the first to depart for urban settlements with the collapse of the nomadic economy in the 1980s. While there is a general correlation based on skin colour, what determines status is a credible lineage that can document noble origins. Thus, one might encounter a Black “white,” and some Ḥarāṭīn might pass for Bīḍān if their name or lineage is unknown.

Roughly one-third of the population is made up of mainly four other ethnic groups: Tukulor, who live in the Sénégal River valley; Fulani, who are dispersed throughout the south; Soninke, who inhabit the extreme south; and Wolof, who live in the vicinity of Rosso in coastal southwestern Mauritania.

The Moors, Tukulor, and Soninke share a broadly similar social structure, in as much as these groups were historically divided into a hierarchy of social classes. At the head of these socioeconomic layers were nobles who had dependents and tributaries, and these “well-born” populations were frequently supported by servants and slaves.

In Moorish society the nobles consisted of two types of lineages: ʿarabs, or warriors, descendants of the Banū Ḥassān and known as the Ḥassānīs, and murābiṭ—called marabouts by the French and known in their own language as zawāyā after the name of a place of religious study (see zāwiyah)—who were holy men and scholars of religious texts. The warriors generally claimed Arab descent, and many of the zawāyā traced their origins to Amazigh lineages. The greatest part of the Bīḍān population consisted of vassals who received protection from the warriors or zawāyā to whom they paid tribute. At the bottom of the social hierarchy were two artisan classes—the blacksmiths and the griots (troubadour-praise singers). Servant classes were subdivided into slaves and freedmen, the Ḥarāṭīn, although their personal autonomy was severely limited in the nomadic economy.

Slavery was abolished by the French in colonial times and has been banned a number of times since independence. The practice persisted, however, and it was not until 2007 that a bill was passed that made slavery a criminal offense. Slavery (and its definition) remains a very sensitive issue for the Mauritanian government, which has long disputed its continued existence in spite of reports to the contrary by international groups. For servants in the rural economy who are dependent upon their masters and who lack the skills necessary to join the urban economy, the line between servitude and freedom is very ambiguous. So long as there is a dependence upon such labour to maintain the Bīḍānī lifestyle, there remain both expectations by the servant classes that their well-being is the responsibility of the well-born and the long-standing cultural assumption among the Bīḍān that Black Africans belong in a servile role. As the old nomadic economy withers away, however, so too this relationship has been gradually disappearing. Since independence there have been sporadic efforts to find common political ground between the Ḥarāṭīn and the other Black populations in the country. Such a coalition would constitute a clear majority of the population, but, to date, political pressure on the Ḥarāṭīn and their cultural and linguistic roots in Bīḍān society have deflected any political configuration based simply on race.

Languages

Arabic is the official language of Mauritania; Fula, Soninke, and Wolof are recognized as national languages. The Moors speak Ḥassāniyyah Arabic, a dialect that draws most of its grammar from Arabic and uses a vocabulary of both Arabic and Arabized Amazigh words. Most of the Ḥassāniyyah speakers are also familiar with colloquial Egyptian and Syrian Arabic due to the influence of television and radio transmissions from the Middle East. One result of Mauritanian Arabic being drawn into the mainstream of the Arabic-speaking world has been a revalorization of Ḥassāniyyah forms in personal names, especially evident in the use of “Ould” or “Wuld” (“Son of”) in male names. The Tukulor and the Fulani in the Sénégal River basin speak Fula (Fulfulde, Pular), a language of the Atlantic branch of the Niger-Congo family. The other ethnic groups have retained their respective languages, which are also part of the Niger-Congo family: Soninke (Mande branch) and Wolof (Atlantic branch). Since the late 1980s Arabic has been the primary language of instruction in schools throughout the country, slowly ending a long-standing advantage formerly held by the French-schooled populations of the Sénégal River valley.

Religion

Almost all Mauritanians are Sunni Muslim. The declaration of the country as an Islamic republic at independence marked a political aspiration that religion might unite very diverse populations under that common confession. Two of the major Sufi (mystical) brotherhoods—the Qādiriyyah and Tijāniyyah orders—have numerous adherents throughout the country, but there is little distinct pattern in the distribution of these groups. Urban religious associations based on place of worship, common hometowns or regions, and ethnicity have flourished throughout the country, and most urban dwellers identify first with their rural origins rather than with the new towns and cities.

Art & Culture of Mauritania

The arts

Moorish society is proud of its nomadic past and its Arab and Muslim heritage and boasts of its appellation “the land of a thousand poets” within the Arab world. The composition and recitation of poetry, both in classical forms and in the Ḥassāniyyah dialect, have traditionally been among the distinguishing marks of high culture in Saharan desert society. Traditional music forms, which still flourish, owe much to Andalusian instrumentation as well as sub-Saharan African motifs and are today increasingly fused with Middle Eastern music, due in part to the pervasive influence of television and radio transmissions from the Arab world. Many of the traditional forms of music and instrumentation are being eclipsed by contemporary musicians. Local Mauritanian recording stars include Dimi Mint Abba, Ouleya Mint Amar Tichit, and Malouma Mint Moktar Ould El Meiddah, better known simply as Malouma, who was elected to the Mauritanian senate in 2007. Within the Mauritanian film world, Med Hondo is one of the best-known artists, but Sidney Sokhona and Abderrahmane Sissako are also well-known names. Despite the flood of new cultural influences that have modified traditional practice, goldsmithing remains a fine art, and the work by local silversmiths is highly prized by Mauritanians as well as visitors. The trade in precious beads, which has medieval origins, is also valued.

Cultural Life

The primary task of Mauritania’s successive governments has been to unify a community of diverse ethnic groups that are hierarchical in social structure and very strongly differentiated. The religion shared by all ethnic groups in the country has served as a centripetal force in creating a national culture. Many of the local barriers to cooperation have been overcome, and traditional regional boundaries have been redrawn.

Moorish women have long held central roles as household managers as well as critical cultural roles as the chief transmitters of Moorish culture, a tradition that has been translated into the modern economy with women playing an active part in government, business and education.

Mauritania celebrates the feasts and holidays observed by other Muslim countries, such as ʿĪd al-Fiṭr, which marks the end of Ramadan, and ʿĪd al-Aḍḥā, which marks the culmination of the hajj. In addition to these, Labour Day is observed on May 1, Africa Day on May 25, and Independence Day on November 28.

Heritage of Mauritania!

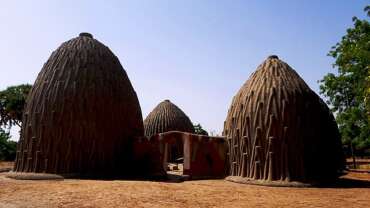

Prehistoric sites and cultural aspects

Mauritania has a rich prehistoric cultural heritage. Engravings and paintings are encountered on privileged sites: higher areas such as the massif of the Mauritanian Adrar and well preserved villages that extend along the cliff of Dhar between Oualata and Tichit which were described in particular by Theodore Monod.

– Tichit

According to the oral tradition re-quoted by renowned historians, the city of Tichitt would have been rebuilt several times on its own ruins. The current city is built on the superimposed rubbles of seven other cities.

Providing, at the beginning, a place of rest for salt caravans crossing the desert between Ouadane, Oualata and Tombuktu, Tichitt became, in the middle of the sixteenth century, an unavoidable step in the caravan route.

– The coastline

The Mauritanian coastline extends nearly from the island of Cap Blanc (Wilaya of Nouadhibou) to the estuary of the Senegal River (Ndiago), on almost 750 km of sandy coast in the form of a succession of beaches suitable for seaside and sports activities development, including big-game fishing and wind surfing.

This is particularly the case of the Banc d’Arguin Park, from Nouamghar to Cape Timiris via Tanit Bay and the Nouakchott area, and to the north of the park around Nouadhibou, where already exist a camp, whose purpose is to host big-game fishermen.

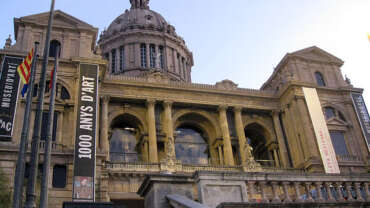

– Oualata

Located in the south-east of Mauritania, 120 km from Néma, Oualata is listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Founded in the 8th century, it is called by the ancient travelers “the shore of eternity”. Its remarkable architecture makes it one of the most beautiful Mauritanian cities.

For centuries, Oualata has also been a spiritual center of Islam. Precious manuscripts are kept there and many students attend classes taught by renowned scholars.

– The inchiri

Located between the Atiantic Ocean in the south-west, and the beautiful regions of Adrar, Tiris, Dakhlet-Nouadhibou in the North and North-East, and the Trarza in the South, the legendary Inchiri region extends over 46800 km2 subjected to the combined influence of the trade winds, the continental trade winds and the monsoon. Along the Amatlich massif, the accumulation of water in the clay zones allows agriculture in the Great Grayrs, despite a climate and relief of Saharan types. The movement of the dunes miraculously makes the wonderful Benichab groundwater with its mineral water renowned and exported outside the country.

– The river

Much of southern Mauritania is bordered by the Senegal River which forms a border of about 800 km that could be the subject of river cruises. The river stretches in the plains of Guidimakha, Gorgol, Brakna and Trarza in the south of the country whose populations ways of life are different from the rest of the country.

The population is rich in its historical diversity: all ethnic groups “Moorish, Peulh, Wolof and Soninké” coexist and melt there harmoniously since centuries…