Jamaica – Once you go, you know

Jamaica, a Caribbean island nation, has a lush topography of mountains, rainforests and reef-lined beaches. Many of its all-inclusive resorts are clustered in Montego Bay, with its British-colonial architecture, and Negril, known for its diving and snorkeling sites. Jamaica is famed as the birthplace of reggae music, and its capital Kingston is home to the Bob Marley Museum, dedicated to the famous singer.

History of Jamaica

The following history of Jamaica focuses on events from the time of European contact. For treatments of the island in its regional context, see West Indies and history of Latin America.

Early period

The first inhabitants of Jamaica probably came from islands to the east in two waves of migration. About 600 CE the culture known as the “Redware people” arrived; little is known of them, however, beyond the red pottery they left. They were followed about 800 by the Arawakan-speaking Taino, who eventually settled throughout the island. Their economy, based on fishing and the cultivation of corn (maize) and cassava, sustained as many as 60,000 people in villages led by caciques (chieftains).

Christopher Columbus reached the island in 1494 and spent a year shipwrecked there in 1503–04. The Spanish crown granted the island to the Columbus family, but for decades it was something of a backwater, valued chiefly as a supply base for food and animal hides. In 1509 Juan de Esquivel founded the first permanent European settlement, the town of Sevilla la Nueva (New Seville), on the north coast. In 1534 the capital was moved to Villa de la Vega (later Santiago de la Vega), now called Spanish Town. The Spanish enslaved many of the Taino; some escaped, but most died from European diseases and overwork. The Spaniards also introduced the first African slaves. By the early 17th century, when virtually no Taino remained in the region, the population of the island was about 3,000, including a small number of African slaves.

British rule

Planters, buccaneers, and slaves

In 1655 a British expedition under Admiral Sir William Penn and General Robert Venables captured Jamaica and began expelling the Spanish, a task that was accomplished within five years. However, many of the Spaniards’ escaped slaves had formed communities in the highlands, and increasing numbers also escaped from British plantations. The former slaves were called Maroons, a name probably derived from the Spanish word cimarrón, meaning “wild” or “untamed.” The Maroons adapted to life in the wilderness by establishing remote defensible settlements, cultivating scattered plots of land (notably with plantains and yams), hunting, and developing herbal medicines; some also intermarried with the few remaining Taino.

A slave’s life on Jamaica was brutal and short, because of high incidences of tropical and imported diseases and harsh working conditions; the number of slave deaths was consistently larger than the number of births. Europeans fared much better but were also susceptible to tropical diseases, such as yellow fever and malaria. Despite those conditions, slave traffic and European immigration increased, and the island’s population grew from a few thousand in the mid-17th century to about 18,000 in the 1680s, with slaves accounting for more than half of the total.

The British military governor, concerned about the possibility of Spanish assaults, urged buccaneers to move to Jamaica, and the island’s ports soon became their safe havens; Port Royal, in particular, gained notoriety for its great wealth and lawlessness. The buccaneers relentlessly attacked Spanish Caribbean cities and commerce, thereby strategically aiding Britain by diverting Spain’s military resources and threatening its lucrative gold and silver trade. Some of the buccaneers held royal commissions as privateers but were still largely pirates; nevertheless, many became part-time merchants or planters.

After the Spanish recognized British claims to Jamaica in the Treaty of Madrid (1670), British authorities began to suppress the buccaneers. In 1672 they arrested Henry Morgan following his successful (though unsanctioned) assault on Panama. However, two years later the crown knighted him and appointed him deputy governor of Jamaica, and many of his former comrades submitted to his authority.

The Royal African Company was formed in 1672 with a monopoly of the British slave trade, and from that time Jamaica became one of the world’s busiest slave markets, with a thriving smuggling trade to Spanish America. African slaves soon outnumbered Europeans 5 to 1. Jamaica also became one of Britain’s most-valuable colonies in terms of agricultural production, with dozens of processing centres for sugar, indigo, and cacao (the source of cocoa beans), although a plant disease destroyed much of the cacao crop in 1670–71.

European colonists formed a local legislature as an early step toward self-government, although its members represented only a small fraction of the wealthy elite. From 1678 the British-appointed governor instituted a controversial plan to impose taxes and abolish the assembly, but the legislature was restored in 1682. The following year the assembly acquiesced in passing a revenue act. In 1692 an earthquake devastated the town of Port Royal, destroying and inundating most of its buildings; survivors of the disaster established Kingston across the bay.

People of Jamaica

Ethnic groups and languages

Spanish colonists had virtually exterminated the aboriginal Taino people by the time the English invaded the island in 1655. The Spaniards themselves escaped the island or were expelled shortly afterward. The population of English settlers remained small, but they brought in vast numbers of African slaves to work the sugar estates. Today the population consists predominantly of the descendants of those slaves, with a small proportion of people of mixed African and European descent. Even fewer in number are people who trace their ancestry to the United Kingdom, India, China, the Middle East, Portugal, and Germany.

English, the official language, is commonly used in towns and among the more-privileged social classes. Jamaican Creole is also widely spoken. Its vocabulary and grammar are based in English, but its various dialects derive vocabulary and phrasing from West African languages, Spanish, and, to a lesser degree, French. The grammatical structure, lyrical cadences, intonations, and pronunciations of Creole make it a distinct language.

Religion

Freedom of worship is guaranteed by Jamaica’s constitution. Most Jamaicans are Protestant. The largest denominations are the Seventh-day Adventist and Pentecostal churches; a smaller but still significant number of religious adherents belong to various denominations using the name Church of God. Only a small proportion of Jamaicans attend the Anglican church, which, as the Church of England, was the island’s only established church until 1870. Smaller Protestant denominations include the Moravian church, the United Church in Jamaica and the Cayman Islands, the Society of Friends (Quakers), and the United Church of Christ. There is also a branch of the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church.

The Jewish community is one of the oldest in the Western Hemisphere. Jamaica also has a small Hindu population and small numbers of Muslims and Buddhists. There are some religious movements that combine elements of both Christianity and West African traditions. The central feature of the Pukumina sect, for example, is spirit possession; the Kumina sect has rituals characterized by drumming, dancing, and spirit possession. Obeah (Obia) and Etu similarly recall the cosmology of Africa, while Revival Zion has elements of both Christian and African religions.

Rastafarianism has been an important religious and cultural movement in Jamaica since the 1930s and has attracted adherents from the island’s poorest communities, although it represents only a small proportion of the total population. Rastafarians believe in the divinity of Emperor Haile Selassie I of Ethiopia and in the eventual return of his exiled followers to Africa. Rastafarianism has become internationally known through its associations with reggae music and some of Jamaica’s most successful musical stars.

Art & Culture of Jamaica

The arts and cultural institutions

The Institute of Jamaica, an early patron and promoter of the arts, sponsors exhibitions and awards. The institute administers the National Gallery, Liberty Hall, the African Caribbean Institute of Jamaica, and the Jamaica Journal. The institute is also the country’s museums authority. The Jamaica Library Service, Jamaica Archives, National Library, and University of the West Indies contribute to the promotion of the arts and culture, as do numerous commercial art galleries. The Jamaica National Heritage Trust is responsible for the protection of the material cultural heritage of Jamaica.

Local art shows are common, and the visual arts are a vigorous and productive part of Jamaican life. Several artists, including the painters Albert Huie and Barrington Watson and the sculptor Edna Manley, are known internationally.

The poets Claude McKay and Louis Simpson were born in Jamaica, and the Nobel Prize-winning author Derek Walcott attended the University of the West Indies in Mona. Jamaican Creole faced decades of disapproval from critics and academics who favoured standard English, but the Panamanian-born author Andrew Salkey and poets such as Louise Bennett-Coverly and Michael Smith made the language an intrinsic part of the island’s literary culture, emphasizing the oral and rhythmic nature of the language.

Jamaican theatre and musical groups are highly active. The National Dance Theatre Company, formed in 1962, has earned international recognition. Much of the country’s artistic expression finds an outlet in the annual Festival. In the 1950s and ’60s Ernie Ranglin, Don Drummond, and other Jamaican musicians developed the ska style, based in part on a Jamaican dance music called mento. Reggae, in turn, arose from ska, and from the 1970s such renowned performers as Bob Marley, Peter Tosh, and Lee Perry made it one of the island’s most-celebrated international exports. Dancehall music—which focuses on a rapping, or “toasting,” deejay—also became popular in the late 20th century. Jamaican musicians release hundreds of new recordings every year. Reggae Sumfest draws large crowds of local and overseas enthusiasts.

Cultural Life

Jamaica’s cultural development has been deeply influenced by British traditions and a search for roots in folk forms. The latter are based chiefly on the colourful rhythmic intensity of the island’s African heritage.

Cultural milieu

Jamaican culture is a product of the interaction between Europe and Africa. Terms such as “Afro-centred” and “Euro-centred,” however, are often used to denote the perceived duality in Jamaican cultural traditions and values. European influences persist in public institutions, medicine, Christian worship, and the arts. However, African continuities are present in religious life, Jamaican Creole language, cuisine, proverbs, drumming, the rhythms of Jamaican music and dance, traditional medicine (linked to herbal and spiritual healing), and tales of Anansi, the spider-trickster.

Daily life and social customs

Family life is central to most Jamaicans, although formal marriages are less prevalent than in most other countries. It is common for three generations to share a home. Many women earn wages, particularly in households where men are absent, and grandmothers normally take charge of preschool-age children. Wealthier Jamaican families usually employ at least one domestic helper.

The main meal is almost always in the evening, because most people do not have time to prepare a midday meal and children normally eat at school. Families tend to be too busy to share most weekday dinners, but on Sundays tradition dictates that even poor families enjoy a large and sociable brunch or lunch, usually including chicken, fish, yams, fried plantains, and the ubiquitous rice and peas (rice with kidney beans or gungo [pigeon] peas). One of Jamaica’s most popular foods is jerk (spiced and grilled) meat.

Clothing styles vary. Rastafarians, who account for a tiny part of the population, typically wear loose-fitting clothing and long dreadlocks, a hairstyle associated with the Ethiopian emperor Haile Selassie I in the early 20th century.

Jamaican independence from Great Britain (August 6, 1962) is commemorated annually. The government sponsors Festival as part of the independence celebrations. Although it has much in common with the region’s pre-Lenten Carnivals, Festival is much wider in scope, including street dancing and parades, arts and crafts exhibitions, and literary, theatrical, and musical competitions. Since the late 20th century, Jamaicans have also celebrated Carnival, typically with costumed parades, bands, and dancing. Emancipation Day is celebrated on August 1.

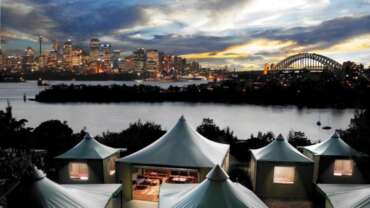

Feel The Rhythm Of Jamaica - the beat, the pulse of life

From each morning’s glorious sunrise until the sea swallows the sun at night, Jamaica presents a magnificent palette of experiences, a kaleidoscope of colors and sounds that make our island the most precious jewel in the Caribbean. We are a land of unique culture, engaging activities, breathtaking landscapes, and a warm, welcoming people.

The beat of reggae. The searing smell of jerk over the fire. The swizzle of rum in your glass. No place on earth provides the range of attractions and the cultural diversity that can be found here. No place on earth feels like it. No place on earth shines like it. Jamaica, the home of rhythm and sway.