Guyana - Nature's beating heart

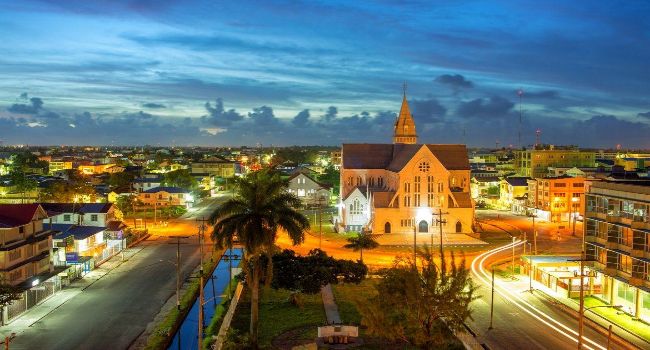

Guyana, a country on South America’s North Atlantic coast, is defined by its dense rainforest. English-speaking, with cricket and calypso music, it’s culturally connected to the Caribbean region. Its capital, Georgetown, is known for British colonial architecture, including tall, painted-timber St. George’s Anglican Cathedral. A large clock marks the facade of Stabroek Market, a source of local produce.

Guyana is an amazing blend of the Caribbean and South America. The name Guyana is an Amerindian word meaning “Land of Many Waters”. Guyana offers a distinct tourism product, consisting of vast open spaces, savannahs, pristine rainforests, mountains, rivers, waterfalls, bountiful wildlife, numerous species of flora, a variety of fauna, spectacular birdlife and most of all the hospitality of the Guyanese people Our beautiful country is a tropical paradise and has much to offer; adventure, tranquility, history, beauty, nature and an inimitable blend of warm and friendly people with the richness of many cultures. Our interior is an eco tourist’s dream with multitude of immense and striking waterfalls, creeks and rivers; virgin rainforest; an abundance of wildlife that includes more than 800 species of birds and over 1000 tree species in its savannahs.

History of Guyana

Early history

The first human inhabitants of Guyana probably entered the highlands during the 1st millennium BCE. Among the earliest settlers were groups of Arawak, Carib, and possibly Warao (Warrau). The early communities practiced shifting agriculture supplemented by hunting. Explorer Christopher Columbus sighted the Guyana coast in 1498, and Spain subsequently claimed, but largely avoided, the area between the Orinoco and Amazon deltas, a region long known as the Wild Coast. It was the Dutch who finally began European settlement, establishing trading posts upriver in about 1580. By the mid-17th century the Dutch had begun importing slaves from West Africa to cultivate sugarcane. In the 18th century the Dutch, joined by other Europeans, moved their estates downriver toward the fertile soils of the estuaries and coastal mud flats. Laurens Storm van ’s Gravesande, governor of Essequibo from 1742 to 1772, coordinated these development efforts.

Guyana changed hands with bewildering frequency during the French revolutionary and Napoleonic wars (mostly between the British and the French) from 1792 to 1815. During a brief French occupation, Longchamps, later called Georgetown, was established at the mouth of the Demerara River; the Dutch renamed it Stabroek and continued to develop it. The British took over in 1796 and remained in possession, except for short intervals, until 1814, when they purchased Demerara, Berbice, and Essequibo, which in 1831 were united as the colony of British Guiana.

British rule

When the slave trade was abolished in 1807, there were about 100,000 slaves in Berbice, Demerara, and Essequibo. After full emancipation in 1838, black freedmen left the plantations to establish their own settlements along the coastal plain. The planters then imported labour from several sources, the most productive of whom were the indentured workers from India. Indentured labourers who earned their freedom settled in coastal villages near the estates, a process that became established in the late 19th century during a serious economic depression caused by competition with European sugar beet production. The importation of indentured labourers from India exemplifies the connection between Guiana’s history and the British imperial history of the other Anglophone countries in the Caribbean region.

Settlement proceeded slowly, but gold was discovered in 1879, and a boom in the 1890s helped the colony. The North West District, an 8,000-square-mile (21,000-square-km) area bordering on Venezuela that was organized in 1889, was the cause of a dispute in 1895, when the United States supported Venezuela’s claims to that mineral- and timber-rich territory. Venezuela revived its claims on British Guiana in 1962, an issue that went to the United Nations for mediation in the early 1980s but still had not been resolved in the early 21st century.

The British inherited from the Dutch a complicated constitutional structure. Changes in 1891 led to progressively greater power’s being held by locally elected officials, but reforms in 1928 invested all power in the governor and the Colonial Office. In 1953 a new constitution—with universal adult suffrage, a bicameral elected legislature, and a ministerial system—was introduced.

From 1953 to 1966 the political history of the colony was stormy. The first elected government, formed by the People’s Progressive Party (PPP) and led by Cheddi Jagan, seemed so pro-communist that the British suspended the constitution in October 1953 and dispatched troops. The constitution was not restored until 1957. The PPP split along ethnic lines, Jagan leading a predominately South Asian party and Forbes Burnham leading a party of African descendants, the People’s National Congress (PNC). The elections of 1957 and 1961 returned the PPP with working majorities. From 1961 to 1964 severe rioting, involving bloodshed between rival Afro-Guyanese and South Asian groups, and a long general strike led to the return of British troops.

Independence of Guyana

To answer the PNC allegation that the existing electoral system unduly favoured the South Asian community, the British government introduced for the elections of December 1964 a new system of proportional representation. Thereafter the PNC and a smaller, more conservative party formed a coalition government, led by Burnham, which took the colony into independence under its new name, Guyana, on May 26, 1966. The PNC gained full power in the general election of 1968, which was characterized by questionable rolls of overseas voters and widespread claims of electoral impropriety.

On February 23, 1970, Guyana was proclaimed a cooperative republic within the Commonwealth. A president was elected by the National Assembly, but Burnham retained executive power as prime minister. Burnham declared his government to be socialist and in the later 1970s sought to reorder the government in his favour. In 1978 one of the most bizarre incidents in modern history occurred in Guyana when some 900 members of a religious community known as the Peoples Temple committed mass suicide in their Jonestown commune at the behest of their leader, Jim Jones.

In 1980, under a new constitution that provided for a unicameral legislature, Burnham became executive president, with still wider powers, after an election in which international observers detected widespread fraud. Two major assassinations also occurred during this time—Jesuit priest and journalist Bernard Darke was killed in July 1979, and prominent historian and political leader Walter Rodney was murdered in June 1980. Many observers accused Burnham of involvement in the killings. In the following years Burnham faced an economy shattered by the depressed demand for bauxite and sugar and a restive populace suffering from severe commodity shortages and a near breakdown of essential public services. Burnham enforced austerity measures, and he began leaning toward Soviet-bloc countries for support. When he died in 1985, Burnham was succeeded by the prime minister, Hugh Desmond Hoyte, who pledged to continue Burnham’s policies. In elections held that year, Hoyte won the presidency by a wide margin, but once again charges of vote fraud were raised.

People of Guyana

Ethnic groups

South Asians form the largest ethnic group in the country, representing about two-fifths of the population. Their ancestors arrived mostly as indentured labour from India to replace Africans in plantation work. Today South Asians remain the mainstay of plantation agriculture, and many are independent farmers and landowners; they also have done well in trade and are well represented among the professions.

Afro-Guyanese (Guyanese of African descent) make up about three-tenths of the population. They abandoned the plantations after full emancipation in 1838 to become independent peasantry or town dwellers. People of mixed ancestry constitute about one-fifth of the population. While every possible ethnic mixture can be found in Guyana, mulattoes (people of mixed African and European ancestry) are the most common.

The indigenous peoples of Guyana constitute about one-tenth of the population. They are grouped into coastal and interior groups. Coastal groups include the Warao (Warrau), the Arawak, and the Carib. Peoples of the interior include the Wapisiana (Wapishana), the Arekuna, the Macusí (Macushí), and many more in the forest areas. The Macusí and the Wapisiana are the most prominent in the Rupununi Savanna region. Sizable concentrations of Indians inhabit the far west along the border with Venezuela and Brazil. They are rarely seen in the populated coastal areas, although some have mixed with the Afro-Guyanese and South Asians. Since 1970, traditional Indian lands near the international borders have come under government control, although Indians continue to hold village lands informally throughout Guyana’s interior. Major concessions to logging and gold-mining companies starting in the late 20th century have damaged the lands and polluted the rivers of many Indian groups, forcing some to leave and seek work in Venezuela and Brazil.

Like the South Asians, many Chinese and Portuguese people also entered Guyana originally as agricultural labourers, but they are now rarely found outside the towns. They are active in business and the professions, and their influence is disproportionate to their numbers; they have not been increasing, however, and together they constitute only a tiny percentage of the population. Brazilians represent a small but growing minority group.

Languages and religion

The official and principal language is English, but a creole patois is spoken throughout the country. Hindi and Urdu are heard occasionally among older South Asians. The major religions are Christian (chiefly Anglican and Roman Catholic) and Hindu. Various forms of Protestant Christianity made inroads in the 20th century, mainly in Georgetown. There is also a sizable minority of Muslims, most of whom are of South Asian descent. Indigenous religions are still practiced by some of the Indian peoples.

Cultural Life of Guyana

Cultural milieu

The national social structure was inherited from the period of British colonial rule, under which the majority of South Asian and Afro-Guyanese labourers were directed by European planters and government officials. A poorly defined local middle class composed of teachers, professionals, and civil servants and including a disproportionate number of Chinese and Portuguese emerged during colonialism. Since independence the elite of the ruling political party has replaced the European plantocracy at the apex of Guyana’s social order. Indigenous peoples remain apart from the country’s social structure as they did under the British, but their culture, which remains uninfluenced by national politics, is recognized as an important element in Guyanese museum displays and as an inspiration in local music and art.

Daily life and social customs

Daily life in Guyana centres on family groups; notably, the matriarchal family among Afro-Guyanese contrasts with the patriarchal South Asian family. Daily dress normally does not distinguish one group from another. Guyana’s cuisine is a blend of South Asian, South American, and Chinese dishes that make liberal use of fiery locally grown chiles and of fresh tropical fruits and vegetables. A typical dish is pepperpot, a stew made of meat (usually beef, mutton, or pork), potatoes, and peppers laced with cassareep (a sauce concocted from cassava juice and spices). The Guyanese advise that anyone who braves the dish should keep a supply of iced beer and locally produced rums nearby.

The arts of Guyana

Arawak and Carib crafts are sold in markets throughout the country. Their brightly coloured textiles, paintings, and intricate baskets are also popular exports.

Guyanese writers have made noteworthy contributions to literature. The works of Wilson Harris, Edgar Mittelhölzer, Walter Rodney, and A.J. Seymour are among the foremost. The best known of them, E.R. Braithwaite, settled in London in the 1950s, and it was there that he wrote his best-selling novel To Sir, with Love (1959), which told of a Guyanese schoolteacher’s adventures in a tough London East End high school. (The movie version [1967] stars Sidney Poitier.) Like Braithwaite, many other 20th-century Guyanese writers emigrated, especially to the United States and England.

Many of Guyana’s leading musicians also have established large followings in the country’s expatriate communities, particularly in London and New York City.

Cultural institutions

Cultural institutions are concentrated in Georgetown. The city’s Guyana Museum includes the Guyana Zoo, which has an impressive collection of animals, including harpy eagles and manatees. The Walter Roth Museum of Anthropology, also in the capital, contains artifacts of the country’s various indigenous cultures. The Guyanese Heritage Museum in Kastev houses a collection of 18th- and 19th-century Guyanese maps, coins, and books. The Rupununi Weavers Society Museum is situated near the town of Lethem on the Brazilian border; it displays textiles made by the Wapisiana and Macusí groups.

Cultural & Heritage Tourism in Guyana

With a vast mix of ethnic backgrounds, traditions, spiritual beliefs, festivals, architecture and landscapes, the memories of Guyana blaze long after travellers have left its shores. The rich cultural landscape of the country can best be explained as a mix of Caribbean culture (found mostly on the coast) and Indigenous roots (found more south in the country), with a dash of its colonial legacy which brought many other nationalities to live in Guyana. It can be experienced by attending festivals, staying with local communities in ecolodges, exploring the architectural heritage of the country, and indulging in Guyanese cuisine.